Lefschetz fixed-point theorem

In mathematics, the Lefschetz fixed-point theorem is a formula that counts the fixed points of a continuous mapping from a compact topological space X to itself by means of traces of the induced mappings on the homology groups of X. It is named after Solomon Lefschetz, who first stated it in 1926.

The counting is subject to an imputed multiplicity at a fixed point called the fixed point index. A weak version of the theorem is enough to show that a mapping without any fixed point must have rather special topological properties (like a rotation of a circle).

Contents |

Formal statement

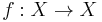

For a formal statement of the theorem, let

be a continuous map from a compact triangulable space X to itself. Define the Lefschetz number Λf of f by

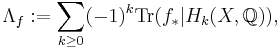

the alternating (finite) sum of the matrix traces of the linear maps induced by f on the Hk(X,Q), the singular homology of X with rational coefficients.

A simple version of the Lefschetz fixed-point theorem states: if

then f has at least one fixed point, i.e. there exists at least one x in X such that f(x) = x. In fact, since the Lefschetz number has been defined at the homology level, the conclusion can be extended to say that any map homotopic to f has a fixed point as well.

Note however that the converse is not true in general: Λf may be zero even if f has fixed points.

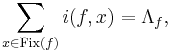

A stronger form of the theorem, also known as the Lefschetz-Hopf theorem, states that, if f has only finitely many fixed points, then

where Fix(f) is the set of fixed points of f, and i(f,x) denotes the index of the fixed point x.[1]

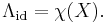

Relation to the Euler characteristic

The Lefschetz number of the identity map on a finite CW complex can be easily computed by realizing that each  can be thought of as an identity matrix, and so each trace term is simply the dimension of the appropriate homology group. Thus the Lefschetz number of the identity map is equal to the alternating sum of the Betti numbers of the space, which in turn is equal to the Euler characteristic χ(X). Thus we have

can be thought of as an identity matrix, and so each trace term is simply the dimension of the appropriate homology group. Thus the Lefschetz number of the identity map is equal to the alternating sum of the Betti numbers of the space, which in turn is equal to the Euler characteristic χ(X). Thus we have

Relation to the Brouwer fixed point theorem

The Lefschetz fixed point theorem generalizes the Brouwer fixed point theorem, which states that every continuous map from the n-dimensional closed unit disk Dn to Dn must have at least one fixed point.

This can be seen as follows: Dn is compact and triangulable, all its homology groups except H0 are 0, and every continuous map f : Dn → Dn induces a non-zero homomorphism f* : H0(Dn, Q) → H0(Dn, Q); all this together implies that Λf is non-zero for any continuous map f : Dn → Dn.

Historical context

Lefschetz presented his fixed point theorem in [Lefschetz 1926]. Lefschetz's focus was not on fixed points of mappings, but rather on what are now called coincidence points of mappings.

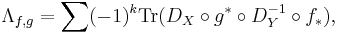

Given two maps f and g from an orientable manifold X to an orientable manifold Y of the same dimension, the Lefschetz coincidence number of f and g is defined as

where f∗ is as above, g∗ is the mapping induced by g on the cohomology groups with rational coefficients, and DX and DY are the Poincaré duality isomorphisms for X and Y, respectively.

Lefschetz proves that if the coincidence number is nonzero, then f and g have a coincidence point. He notes in his paper that letting X = Y and letting g be the identity map gives a simpler result, which we now know as the fixed point theorem.

Frobenius

Let  be a variety defined over the finite field

be a variety defined over the finite field  with

with  elements and let

elements and let  be the lift of

be the lift of  to the algebraic closure of

to the algebraic closure of  . The Frobenius endomorphism (often just the Frobenius), notation

. The Frobenius endomorphism (often just the Frobenius), notation  , of

, of  maps a point with coordinates

maps a point with coordinates  to the point with coordinates

to the point with coordinates  (i.e.

(i.e.  is the geometric Frobenius). Thus the fixed points of

is the geometric Frobenius). Thus the fixed points of  are exactly the points of

are exactly the points of  with coordinates in

with coordinates in  , notation for the set of these points:

, notation for the set of these points:  . The Lefschetz trace formula holds in this context and reads:

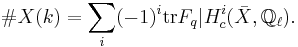

. The Lefschetz trace formula holds in this context and reads:

This formula involves the trace of the Frobenius on the étale cohomology, with compact supports, of  with values in the field of

with values in the field of  -adic numbers, where

-adic numbers, where  is a prime coprime to

is a prime coprime to  .

.

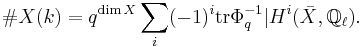

If  is smooth and equidimensional, this formula can be rewritten in terms of the arithmetic Frobenius

is smooth and equidimensional, this formula can be rewritten in terms of the arithmetic Frobenius  , which acts as the inverse of

, which acts as the inverse of  on cohomology:

on cohomology:

This formula involves usual cohomology, rather than cohomology with compact supports.

The Lefschetz trace formula can also be generalized to algebraic stacks over finite fields.

See also

Notes

- ^ Dold, Albrecht (1980). Lectures on algebraic topology. 200 (2nd ed.). Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-10369-1. MR606196, Proposition VII.6.6.

References

- Solomon Lefschetz (1926). "Intersections and transformations of complexes and manifolds". Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 28 (1): 1–49. doi:10.2307/1989171.

- Solomon Lefschetz (1937). "On the fixed point formula". Ann. of Math. 38 (4): 819–822. doi:10.2307/1968838.